On this page: Indigenous Nursing leaders, The intersection of nursing and Indigenous Peoples, historically and present day, Reports, and Tools for Being a Change Agent.

Indigenous Nursing Leaders

Jean Cuthand Goodwill was one of the first Indigenous registered nurses in Canada. In 1974, she cofounded what is now the Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association. She was a lifelong organizer, writer and educator who promoted First Nations health and culture.

Jean Cuthand Goodwill, taken when she was head nurse in La Ronge, SK, in 1958. Photo courtesy Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan/R-B6085

“Ninanâskomânânak kâkînîkânohtêcik”: “We are grateful to the first leaders”. This publication celebrates Indigenous nurses (from 1975-2015) who have been recognized in their communities and nationally, and have taught us concepts of culture, Indigeneity, colonization, reconciliation, equity, and resilience as part of a culturally safe approach in health care.

University of Saskatchewan Indigenous Alumni Video Series.

This video series asks a series of University of Saskatchewan Indigenous and Métis Nursing alumni the important question: What do you love about nursing?

History and Present Day: The Intersection of Nursing and Indigenous Peoples

Nursing, Truth, and Reconciliation

In order to understand and address the harms of colonization, the nursing profession must recognize its role within colonial health systems that have and continue to perpetuate harm.

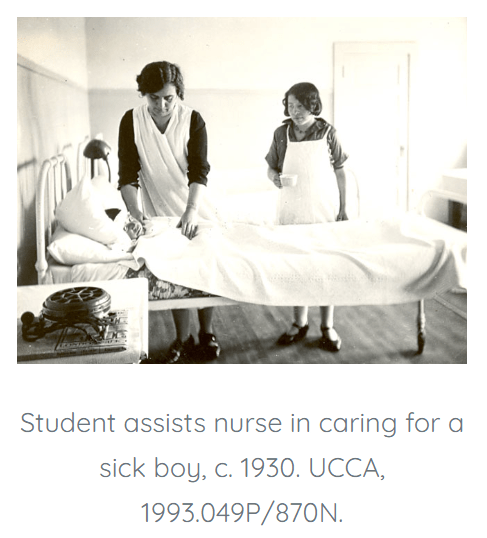

In Indian hospitals, nurses worked as managers, in nursing care, and as nursing students although unlike settler hospitals, nurses working in Indian hospitals were not required to maintain licensure and rarely worked within nursing practice standards or ethics.

Nurses also worked at Indian Residential Schools where they participated in experiments without consent or knowledge from either children or their parents. Many children died from these experiments during their time at the schools, or shortly thereafter. Nurses also took a role as Indian agents to remove children from their homes and take them to residential schools or as “cases” for Indian hospitals.

Nurses also participated in forced sterilization and other reproductive interventions, including unethical and targeted birth control and abortions. The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (Vol 1a, 2019, ppl 53, 266 and 267) highlighted that official policies of sterilization emerged in the 1920s as part of the eugenics movement and formed part of a genocidal policy against Indigenous peoples. Coerced sterilization is an issue that is contemporary as well as historical. (See the report, Coerced Tubal Ligations in Saskatoon, 2017.)

It is undeniable that nurses were an integral part of the colonial project in both residential schools and the Indian hospitals. Thus, all nurses have inherited this history and the legacy of having mistrust as a current challenge when interacting with First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples.

For more information see: Bourque Bearskin, D. H., et al.(2020). In search of the truth: Uncovering nursing’s involvement in colonial harms and assimilative policies five years post truth and

reconciliation commission. Witness: The Canadian Journal of Critical Nursing Discourse, 2(1), 84-96.

Standing Committee on Human Rights. (2022) The Scars that We Carry: Forced and Coerced Sterilization of Persons in Canada – Part II.

I refuse to use the excuse I didn’t know about the Indian Residential Schools Anymore (Ashley Holloway, Alberta Association of Nurses)

The Indian Hospital System

The Fort Qu’Appelle Indian Hospital was opened in 1909 as a 50-bed segregated Tuberculosis facility for First Nations and Métis patients. Read more here.

The legacy of the Indian hospitals are still present today in our health system – as “a system developed under the promise of health care in the face of rising tuberculosis rates that instead delivered segregation, isolation, and pain.” Read more here.

Separate Beds by Maureen K. Lux is the shocking story of Canada’s system of segregated health care. Operated by the same bureaucracy that was expanding health care opportunities for most Canadians, the “Indian Hospitals” were underfunded, understaffed, overcrowded, and rife with coercion and medical experimentation.

Reports

In Plain Sight Report

In Plain Sight is a report on the investigation conducted by former judge Dr. Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond in response to disturbing reports of racism, stereotyping and discrimination against Indigenous peoples in the B.C. health care system. It is based on consultations with nearly 9,000 people, including 2,780 Indigenous people and 5,440 health care workers.

Coerced Tubal Ligations in Saskatoon

On July 27, 2017, the Saskatoon Health Region admitted it failed Indigenous mothers in the community after Indigenous women reported they were coerced to have a tubal ligation. Indigenous women said they went to Royal University Hospital in Saskatoon to have a baby and were pressured into having a sterilization procedure during labour. Seven women were interviewed for this report by Drs. Yvonne Boyer and Judith Bartlett.

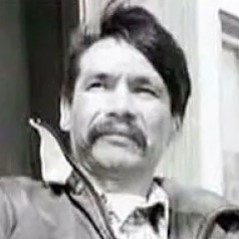

Brian Sinclair

Brian Sinclair died in September 2008 in the emergency department waiting room of Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre. An autopsy later found that Mr. Sinclair, 45, had a treatable bladder infection brought on by a blocked catheter. Testimony later revealed that Mr. Sinclair arrived at hospital with a note from a walk-in clinic explaining his condition. Despite that, he was never triaged and was instead sent to the waiting room. During his time in the waiting room, security staff or other patients in the waiting room raised concerns about his condition to nursing staff, but were ignored. Coroners estimated Mr. Sinclair had been dead for between two and seven hours before someone noticed. Read Brenda Gunn’s paper on how systemic racism played a part in Mr. Sinclair’s death here. The Canadian Medical Association Journal’s article on Mr. Sinclair’s death can be found here.

Joyce Echaquan

Joyce Echaquan was a 37-year-old Atikamekw woman who died after seeking treatment for stomach pain at Joliette hospital, about 70km from Montreal. She filmed herself in her hospital bed screaming and calling for help. In the video, live-fed to Facebook in September 2020, two members of staff can be seen insulting her. The autopsy later revealed she died of excess fluid in her lungs. Staff at the hospital had incorrectly assumed she was suffering from a narcotics withdrawal. The coroner reported that Ms. Echaquan, who had heart problems, had been “infantilised” and labelled as a drug abuser by healthcare staff despite there being no evidence to support this. The coroner’s report (translated from French) can be read here.

Marcia Anderson, MD is Cree-Anishinaabe and grew up in the North End of Winnipeg. She has family roots in the Norway House Cree Nation and Peguis First Nation in Manitoba.

Read Dr. Anderson’s article, Legacy of racism, residential schools in health care (2021). In it she refers to the poor care her father received due to racist assumptions in an emergency department, and which he only survived because she was a second year resident at the hospital and could intervene on his behalf. You can listen to her story here at the CBC archives, on the show White Coat Black Art.

In order to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission created 94 Calls to Action (CTAs). The CTAs are actionable policy recommendations meant to aid the healing process in two ways: acknowledging the full, horrifying history of the residential schools system, and creating systems to prevent these abuses from ever happening again. CTAs 18-24 specifically address health care. Ultimately, these recommendations will contribute to health systems free of racism and discrimination and will lead to better health and wellness outcomes for Indigenous Peoples.

TRC Calls to Action

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Calls to Action that pertain to healthcare are on page 7-8 of this report, items 18-24.

“No health-care worker got up in the morning and said, ‘Gee, I think I’ll discriminate against an Indigenous family today’…. That never happens. We have to understand the context for this.” – Cheryl Ward, B.C. provincial lead for the San’yas Indigenous Cultural Safety Program

Being a Change Agent

Dr. Holly Graham, Indigenous Research Chair in Nursing at the College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, partnered with the CRNS to create the following videos on nursing and reconciliation. “Through collaboration with employers, educators, regulators, direct care providers, leaders, and members of the public from across the province, this video represents a heartfelt apology to the Indigenous Peoples of this nation. It’s a testament to our commitment to lead the journey toward reconciliation.” – CRNS, 2023

A Commitment to Truth and Reconciliation (7 minute YouTube video)

Shorter videos: Video 1 (Judy Pelly, Knowledge Keeper; Lynsay Nair, LPN; Cassandra Leggot, NP; Tina Campbell, RN; Cindy Smith, RN)

Video 2 (Jann-Lea Yawney, RN; Michael McFadden, NP; Kathy Chabot, RN; Dr. Solina Richter, RN; Leah Thorpe, RN)

Video 3 (Cindy Smith, RN; Tracy Muggli, Social Worker)

Video 4 (Dr. Cheryl Pollard, RN, RPN; Barbara MacDonald, RN; Christa McLean, RN; Moni Snell, NP; Dr. Mary-Ellen Walker, RN & Council Members)

Video 5 (Andrew McLetchie, RN; Carmen Levandoski, RN; Doug Finnie, Council for CRNS; Mariam Nganzo, RN)

Video 6 (Beverly Balaski, NR; Kendra McKay, NP)

Music: O Siem was written by Susan Aglukark in 1995. O Siem, meaning a joyful greeting for family and loved ones, is “an anthemic call to turn away from racism and prejudice” according to Historica Canada.

Being a Change Agent: Tools

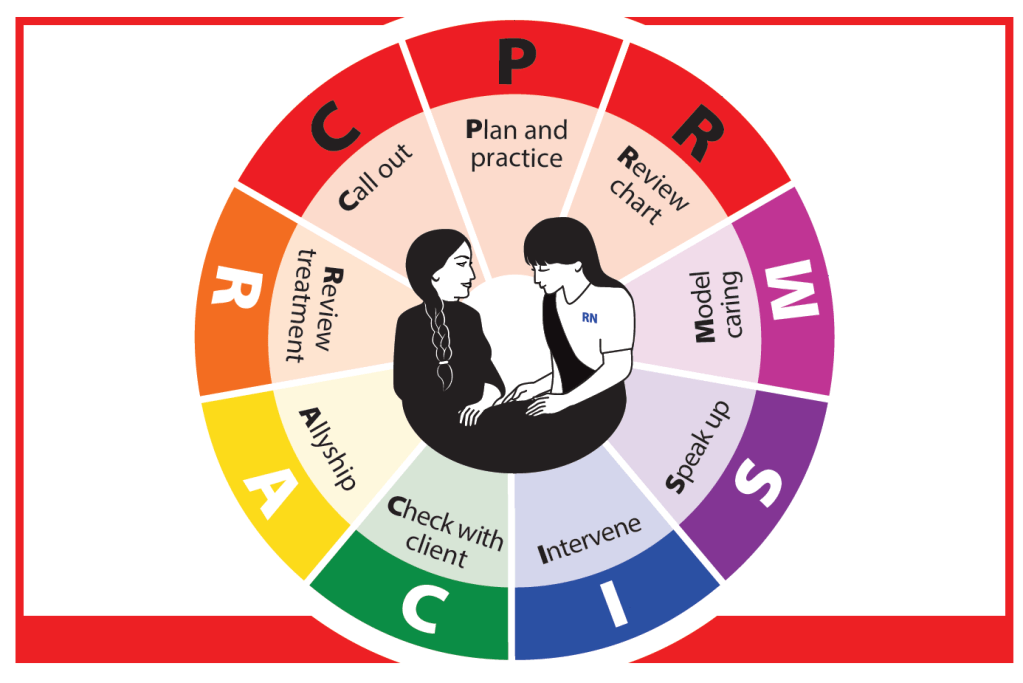

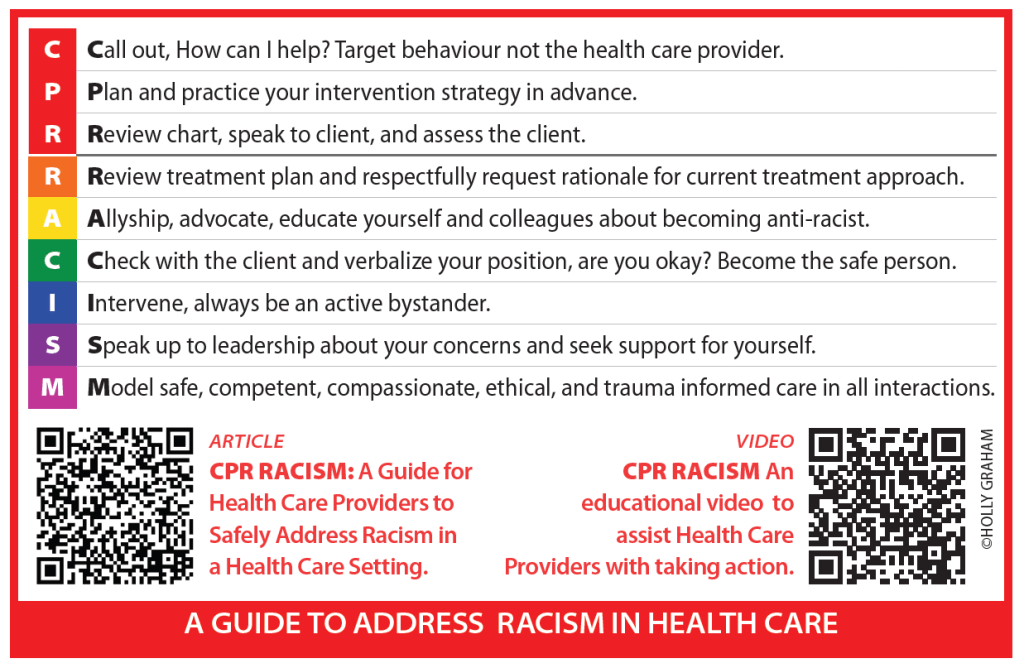

CPR RACISM

Health care providers are all familiar with cardiopulmonary resuscitation

(CPR), capable of saving a life during cardiac arrest. CPR RACISM was chosen as a way to underscore the urgency of addressing racism in health care with similar urgency, because similar to cardiac arrest, racism kills.

Dr. Holly Graham created the CPR RACISM guide in response to the common questions heard from nursing students and professionals: Where do I begin? How can I address racism in healthcare? How do I teach my nursing students to effectively intervene when they witness racism?

Download the article for CPR RACISM here. See also the educational video developed by the CRNS, in collaboration with Dr. Holly Graham, Associate Professor and Indigenous Research Chair in Nursing at the University of Saskatchewan, to assist RNs and NPs with taking action when racism occurs in healthcare settings.

Download the pdf for the above graphic here.

We would be grateful if you would complete this evaluation form of the CPR RACISM guide if you are using it in your practice. Please download it here; it can be filled out on your computer and emailed to the author, whose email is on the form.

The Provider Alliance Scale

The Provider Alliance Scale (PAS) is a tool for health care providers to receive instant feedback from their clients on whether they are forming effective therapeutic relationships that address issues from the client’s perspective, which is a fundamental part of providing patient-centered care and assessing culturally safe care. The PAS assesses four areas: the relationship, communication, partnership, and treatment. The purpose of the measure is to quickly engage patients in their healthcare as true partners, hopefully improving both communication and outcomes.

References:

Graybeal, C., DeSantis, B., Duncan, B. L., Reese, R. J., Brandt, K., & Bohanske, R. T. (2018). Health-related quality of life and the physician–patient alliance: a preliminary investigation of ultra-brief, real-time measures for primary care. Quality of Life Research, 27(12), 3275–3279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1967-4

Indigenous Allyship Toolkit

This toolkit from the Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant Indigenous Health Network was written for health care providers and includes understanding how the colonial relationship affects health care relationships today, understanding and acknowledging bias, and what to do when witnessing discrimination.

The Legacy of Hope Foundation is a national Indigenous charitable organization with the mandate to educate and create awareness and understanding about the Residential School System. This sixteen page guide provides information on what an ally is, why it’s important, the meaning of Reconciliation and so much more.

EQUIP Health Care

EQUIP Health Care, San’yas Anti Racism Indigenous Cultural Safety Program (2022). Rate Your Organization : Addressing Anti Indigenous Racism . A Discussion Tool. Vancouver, BC. Retrieved from www.equiphealthcare.ca

Equity Walkthrough:

Find tools here : https://equiphealthcare.ca/resources/equity-walk-through/

Articles

Quality Advancement in Nursing Education Special Issue:

Indigenous Wellness and Equity with Communities, Students, and Faculty: A Critical Conversation in Nursing Education – Volume 8, Issue 2 (2022)

This special issue contains:

- Shifting Nursing Students’ Attitudes towards Indigenous Peoples by Participation in a Required Indigenous Health Course by R. Cameron and K. Mitchell

- A Nurse’s Journey with Cultural Humility: Acknowledging Personal and Professional Unintentional Indigenous-specific Racism by D. Schmalz, H. Graham & A. Kent-Wilkinson

- File of Uncertainties: Exploring student experience of applying decolonizing knowledge in practice by T.J. Braithwaite, L. Poitras Kelly, & C. Chakanyuka

- The Importance of Being Uncomfortable and Unfinished by C. Foster-Boucher, J. Nelson, S. Bremner, & C. Maykut

- “All My Relations”: Elders’ Teachings Grounding a Decolonial Bachelor of Nursing Program Philosophy by A. Kennedy, L. Headley, E. Van Den Karkhof, G. Harvey, A. Riyaz, R. Dillon, Grandmother D. Spence & Elder R. Bear Chief

- Relational Accountability: A Path Towards Transformative Reconciliation in Nursing Education by J.E. Fraser

- Academic Allyship in Nursing: Deconstructing a successful community-academic collaboration by J. Hickey, M. Crawford, & P. McKinney