The Residential School System in Canada

The term residential schools refers to an extensive school system set up by the Canadian government and administered by churches that had the nominal objective of educating Indigenous children but also the more damaging and equally explicit objectives of indoctrinating them into Euro-Canadian and Christian ways of living and assimilating them into mainstream white Canadian society. The residential school system officially operated from the 1880s into the closing decades of the 20th century.

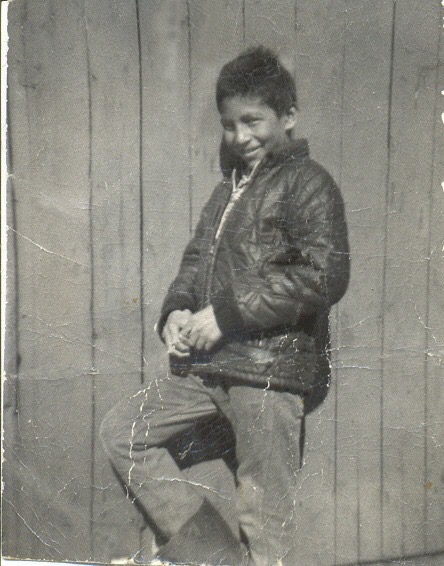

The system forcibly separated children from their families for extended periods of time. In 1920, under the Indian Act, it became mandatory for every Indigenous child to attend a residential school and illegal for them to attend any other educational institution. Children were punished for speaking their own languages, and mistreatment and psychological and sexual abuse were rampant. Many children were starved, and even died while at the schools.

Residential schools did not receive the same level of funding as the public school system. The schools were supposed to largely self-fund by having students attend class part-time and work for the school the rest of the time. Girls were required to cook and clean while the boys performed agricultural and carpentry work. With so little time spent in class, most students had only reached a grade five level by the time they were 18.

The residential school system is viewed by much of the Canadian public as part of a distant past, but for Indigenous people the trauma is very present in their daily lives. Many of the leaders, teachers, parents, and grandparents of today’s Indigenous communities are residential school survivors. Survivors and their descendants share in the intergenerational effects of transmitted personal trauma and loss of language, culture, traditional teachings, and mental/spiritual wellbeing.

The residential schools heavily contributed to educational, social, financial and health disparities between Indigenous Peoples and the rest of Canada, and these impacts continue.

Below are some resources for further information on residential schools, stories of resistance, and resources on healing and moving forward.

Resources

Shattering the Silence: The Hidden History of Indian Residential Schools in Saskatchewan

This is a free ebook you can download on your device. It contains a wealth of resources for adults, youth, children and students, links to professional development, curricular connections and inquiry starters. Although focused on Saskatchewan, resources and understandings presented are universal.

Residential Schools: A timeline

This timeline was compiled by John Edmond for Law Now. It conveys, by historic milestones, how the Indian Residential School system came to be, how it embodied attitudes of its time, how critics were dismissed, and how, finally, the deep harm it did to many Indigenous children and the generations that came after.

A knock on the door: the essential history of residential schools

This book is one of a number recommended by The Canadian Museum for Human Rights‘ webpage on Canada’s Residential Schools.

The Survivors Speak: A Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) provided those directly or indirectly affected by the legacy of the Indian Residential Schools system with an opportunity to share their stories and experiences. This is one of several reports that came out of the TRC Commission’s work.

Crimes against children at residential school: The truth about St. Anne’s: The Fifth Estate

St. Anne’s Indian Residential School in Northern Ontario was a place of horrific abuse and crimes against children that took place over decades. For years, records detailing the abuse were kept hidden from survivors, who needed them for their compensation claims. The existence of these records were even denied by the government.

The Witness Blanket

Inspired by a woven blanket, the Witness Blanket is a large-scale work of art. It contains hundreds of items reclaimed from residential schools, churches, government buildings and traditional and cultural structures from across Canada. You can look at and interact with the blanket online, and it is recommended you watch the documentary as well.

See the videos listed in the Resources page as well.

TRC Reports

Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reports can be found at this link. Further reports include Canada’s Residential Schools: The Inuit and Northern Experience and Canada’s Residential Schools: The Métis Experience.

Stories of Resistance

Heritage Minutes: Chanie Wenjack

The story of Chanie “Charlie” Wenjack, whose death sparked the first inquest into the treatment of Indigenous children in Canadian residential schools. The 84th Heritage Minute in Historica Canada’s collection.

See also Stories of Resistance from The Canadian Encyclopedia.

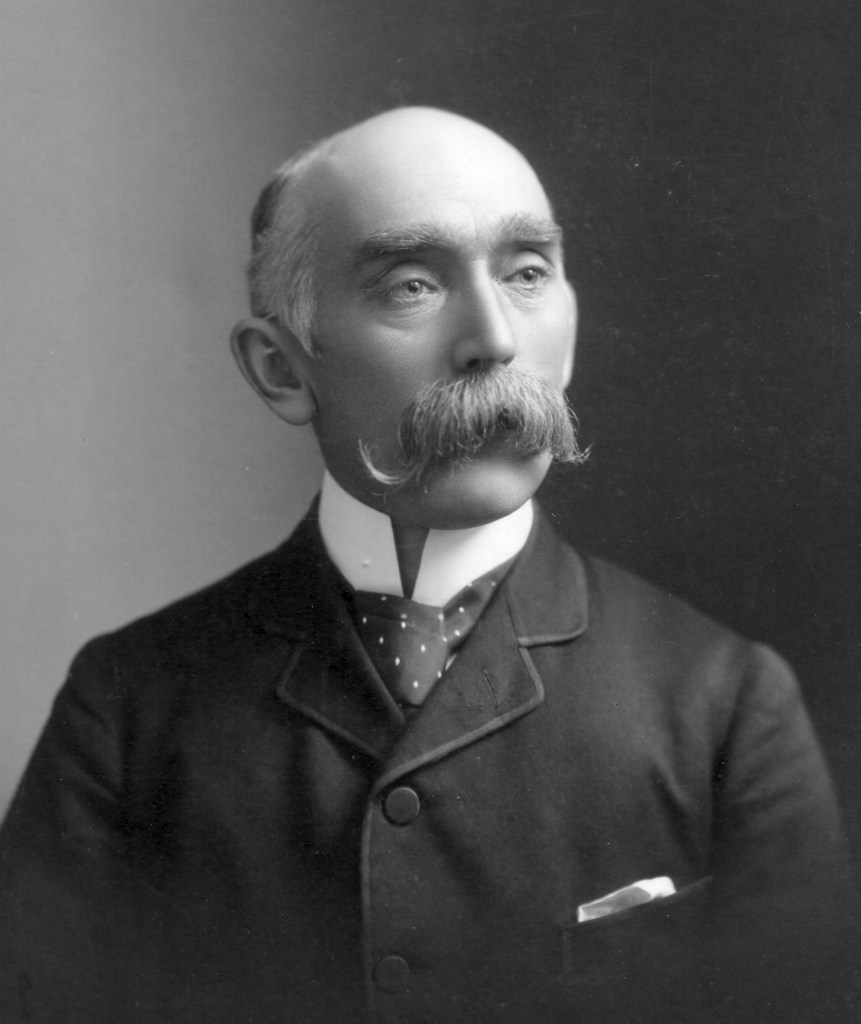

Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce was a Canadian doctor and a leader in the field of Public Health at the turn of the 20th century. He documented and released evidence of the rate of Indigenous children who were dying in residential schools, many who had come to the school healthy, but were then exposed to children with tuberculosis in the poorly ventilated buildings. Dr. Bryce spoke out against the people who were running these schools, including the Canadian government. Dr. Bryce called repeatedly upon Duncan Campbell Scott, federal Deputy Superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs, to improve conditions in the schools, but his recommendations came into direct conflict with Scott’s work to reduce the spending of the Department of Indian Affairs. In 1913, Scott suspended the funding for Bryce’s research on child deaths in residential schools and blocked Dr. Bryce’s presentations of his research findings at academic conferences. Read more about Dr. Bryce here. Dr. Bryce’s 1922 report can be accessed here: The story of a national crime: being an appeal for justice to the Indians of Canada; the wards of the nation, our allies in the Revolutionary War, our brothers-in-arms in the Great War

Healing and Moving Forward: Indigenous Solutions

Promising Healing Practices in Aboriginal Communities

The Aboriginal Healing Foundation was created in 1998 with a mission to support Indigenous people in building and reinforcing sustainable healing processes. Since its inception, an increasing number of Indigenous people have designed, delivered and participated in healing programs. This report looks at the evaluations into what approaches to healing are working especially well and why. The results, presented in this report, are based on the perspectives of more than 100 AHF-funded project teams.

Residential School Crisis Line

Please contact the 24 Hour Residential School Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419 if you require emotional support.

Reclaiming Connections: Understanding Residential School Trauma Among Aboriginal People

Reclaiming Connections is an manual intended to help in understanding the experience of residential school trauma for Indigenous people.